Behavioural Finance: Invest Beyond Emotions

October 13, 2020

6 min

Behavioural finance demonstrates how, in situations of uncertainty and risk, irrationality strongly influences our choices.

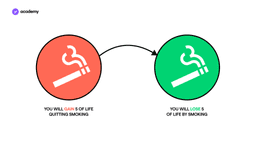

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is one of the behaviour patterns that have the greatest impact on investors’ choices.

It manifests itself in those who avoid situations perceived as “risky”, although they have two possible alternatives: that of gain and that of loss.

Loss Aversion for investors

This cognitive prejudice leads people to avoid investments, without even trying to understand their methods and opportunities. Many people prefer to prevent a loss rather than to make a profit. Therefore, they tend to give up a statistically advantageous investment because the mere idea of losing the investment is too frightening. This fear obscures their ability to judge an asset based on “opportunity costs”.

Losses loom larger than gains

In any case, if our propensity to risk is so low that we cannot bear the loss, it is advisable to consider carefully whether to undertake an investment path. As we have seen, every investment has a more or less high percentage of risk and is never exempt from it.

Overconfidence

The concept of self-deception is a limit to our opportunities to learn. When you mistakenly think you know more than you really know, you tend to lose sight of the information you need to make a conscious decision. When you rely solely on your intuition and superficial notions to make predictions we speak of overconfidence.

Markets are not an entrenched reality, instead they are continuously influenced by external and internal factors that must be monitored. Believing that we can seize every opportunity is the worst chimera to base our financial choices on.

Mental accounting

The mental accounting theory suggests that we mentally allocate money using criteria related to its origin or use. We assign a certain function to each amount and consider them in separate compartments.

Mental accounting has been widely studied by behavioral finance, particularly by Richard Thaler, Nobel Prize winner for economics in 2017.

The crazy thing is thinking humans act logically all the time.

The Dowry Effect

Among the most common effects of mental accounting, there is the dowry effect. The dowry effect shows that people are more likely to retain an object they own than to acquire something new.

To better understand this seemingly trivial behaviour pattern, here’s a rather famous example.In a class of students were given some mugs with the logo of the university they were attending. After a survey, it emerged that those who had received the cup were ready to give it to their classmates for 6 dollars. Those who had not received it declared that they wanted to buy it for no more than 2 dollars.

According to behavioural finance experts, this error stems from our natural loss aversion. To separate ourselves from something that we owe is in its own way painful, therefore we demand a reward greater than the intrinsic value of the good.

A further distortion to take into account derives from the source of the money we are investing. For example, if the money you use has been “won”, you tend to pay less attention to how it is managed.

Age: the tie-breaker

Like everything that is human, markets change. Some profitable investments may not be such in twenty years. That’s why getting attached to an asset you’ve invested in is exactly what you need to avoid. Remaining stubbornly faithful to an investment is another bias that behavioural finance teaches us to avoid.

It’s advisable to make a periodic rebalancing of your portfolio. You need to reallocate your capital by analysing the pros and cons of each change, while remaining faithful to your initial strategy.

One factor affecting the status quo, for example, is age. At every stage of life, we are driven to invest for different reasons and with different objectives. For example, when you are young, you may need an income to finance your studies or to travel abroad. In this case, high-risk assets are preferred, as they can generate a high return in the short term.

At the height of your working career, however, when you are close to receiving the maximum income, you have clearer long-term objectives and fixed expenses, for example a mortgage, children’s tuition fees, dependent parents. That’s when it may make sense to vary your investment portfolio with more low-risk assets while investing a slightly larger capital to consequentially get a higher yield.

Lastly, when you reach the middle age, you are usually freer from fixed expenses and can opt for more secure yields. These allow you to take little risk and prioritise asset protection, maximizing incomes.

Conclusion

The biases identified by behavioural finance and analysed in this article break one of the key rules of economics: the measurement of opportunity cost. All we have left to do it to stay focused on investment evaluations, especially in times of crisis. If we are smart and wise, we will be able to grasp when these biases manipulate the market and to exploit them to our advantage.