P2P and Decentralisation in the Blockchain

May 25, 2020

7 min

One of the most discussed issues in recent years is data collection. At no other time in history has such a large amount of personal data been collected, stored, analysed. So much so that it has become a new form of currency. These concern, for example, the purchasing habits or financial possibilities of the individual.

This indiscriminate and arbitrary monitoring attitude has led to a growing mistrust of people in who should represent their rights (from politics to financial intermediaries) and in the service providers (online and others) that are part of our daily life. Furthermore, this trust is also undermined by the degree of reliability of these third parties: the use they make of our data, the manipulation of information for propaganda purposes, rigged elections, false profiles, scams, etc.

The process of data collection and storage is a reflection of a hierarchical approach between two entities with strong power asymmetries: on the one hand, the authority that takes the data in exchange for a service (company, bank or government), on the other hand, the individual.

This hierarchy is typical of centralised systems.

In the last 20 years, the Internet has overturned the hierarchical approach to information storage and sharing, thus resulting in a change in expectations also with regard to other forms of data storage and disclosure.

Society is moving from hierarchical models to network models. It is a movement from centralised institutions based on mandatory trust to networks built on distributed democracy.

As Vitalik Buterin, founder of Ethereum, argues: “Only by making technical systems that offer a variety of mechanisms for checking concentrations of power and by simultaneously building social ideologies constantly on the lookout for failure modes of these mechanisms can we hope to succeed where previous attempts at decentralizing authority have failed.”

These changes were triggered by the use of internet-based technologies that do not require traditional intermediaries and can be grouped into three phenomenological categories:

- participatory cultures

- peer-to-peer networks

- trust through calculation

Participatory Cultures: P2p Culture

The rise of social platforms, as well as the Internet in a broader sense, make participatory cultures a new instrument of power. These cultures have created in people the expectation of being actively involved in decision-making processes that influence the evolution of social ties, communities, knowledge systems and organisations, as well as politics and culture. In other words, participatory cultures have promoted a new distribution of decision-making power, no longer centralised but decentralised.

Participatory cultures are a reflection of the values of the societies in which they operate. While it is true that in Western and capitalist cultures the emerging media sector – such as social networks giants – has become an engine of commerce, consensus and control, it has also had positive consequences in the communities it has created or awakened. These benefits are community education and mobilisation.

The individual acts and defends his or her interests as an individual, while at the same time taking part in a system by identifying with the general interests of the community. A recognised example of this is the Arab Spring, where the use of tools such as blogs and social media has created a widespread and resilient political momentum. The 2010 uprising shows how these tools and the ability to share information have consequences that are at the root of all decentralised systems:

- they are an aggregator of energies towards a goal;

- they are resistant to government and police infiltration trying to control networks;

- they give a new centrality to the individual who, by choice, operates in the interest of the crowd (or community) created by connecting with other individuals online.

P2p networks

Together with participatory cultures, we have witnessed the growth of peer-to-peer technologies, that are the technological translation of these cultures.

P2P architecture became popular in the 1990s with file-sharing programs such as BitTorrent. In a P2P network, the reputation of those who participate in the network is crucial, as demonstrated by sharing services such as Uber or Airbnb. The difference between these models and a real P2P is the definitive elimination of the intermediary, i.e. the company that regulates the relationship between us and the Uber driver or between us and the Airbnb owner.

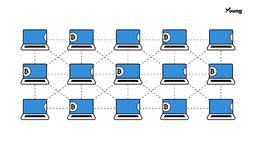

At the base, peer-to-peer technologies create a network of devices (peers) that collectively store data. Each device acts individually but only in the interest of the community. This is because all peers share the same power within the network, the same tasks, and they all have a copy of the archived data. P2P networks are, for the most part, decentralised.

Decentralised P2P networks, therefore, use the community as a decision-making body and this ensures a secure and transparent process. With P2P networks, the authenticity of data is no longer entrusted to humans. Instead of institutional trust, we have a kind of “computational trust“. The trust in the system is not placed on a human act, but is instilled by the reliability of the devices (nodes) that solve complex algorithms to legitimise and record a transaction.

This type of network is in contrast with centralised networks, where the decision-making process is hierarchical and involves filtering and classification of data. Irresponsible centralised parties have the power to modify the terms and conditions of the relationship with other participants at their discretion, which cannot happen for a decentralised network.

The Blockchain: a P2p Network

In finance, peer-to-peer systems are used to exchange cryptocurrency and digital assets.

By applying the peer-to-peer system, the blockchain represents the “promise that one can be actively involved with others in decision-making processes”. The consensus mechanism on which it is based makes the blockchain a decentralised and distributed system.

Decentralisation gives the blockchain a number of strategic advantages:

- Fault tolerance: since the blockchain is based on the operation of a multitude of nodes around the world and does not have a single point of failure, it is virtually impossible for it to be damaged or its operation to be interrupted.

- Resistance to attack: Decentralisation makes it very difficult for hackers to attack the system, as they would have to take control of many nodes at once in order to do the least damage.

- Resistance to collusion: It is highly unlikely that participants in a decentralised system would collude over selfish goals because they would lose all the benefits of collaboration and community. In a centralised system, on the other hand, large corporations at the top are able to lobby for their interests.

Conclusion

Thanks to the blockchain, we understand that when the filing and storage of data is entrusted to a central authority, such as a government, business, charity, church, bank or other:

- it can influence how the data is recorded;

- it may be corrupt;

- it may act in its own interest;

- it keeps the data log exclusively. If that log is stolen or hacked, the data will be lost or manipulated.

These problems, especially with regard to financial issues, have brought about the idea of registers based on decentralised systems. In such systems, registries are considered authentic by virtue of the consensus of the community (consisting of thousands of connected devices):

- trust is given by the reliability of devices (e.g. computers) that are independent of any human activity.

- the reliability of the data is greater because for the data to be recorded it must be approved by a larger number of nodes and the probability of it being corrupted by the minimum of 51% is very low

- each node has a copy of the information log, any manipulation of information would be immediately obvious

- any change in the rules defining the relationship between nodes must be decided by the majority (it is not imposed “from above”)