Proof-of-Stake vs Proof-of-Work: Consensus Mechanisms on Blockchain

October 28, 2021

9 min

Consensus mechanisms such as Proof-of-Work and Proof-of-Stake govern the verification processes of transactions on blockchain. These mechanisms are designed to solve the security problems associated with decentralised systems.

Consensus on Blockchain

A distributed and decentralised system is a set of peers (nodes) with a common purpose. Whether centralised or not, let’s start by stating that no system is free of faults.

The blockchains we are interested in, i.e. permissionless and decentralised ones, have the purpose of validating cryptocurrency transactions and adding them to the blockchain in a correct and functional way.

While payment systems such as Visa manage the validation of transactions centrally, acting as the main intermediaries, on these blockchains, there is no authority, i.e. one node of the network with more control than the others.

This is why blockchains have had to find ways of giving equal power to all participants while avoiding harmful practices such as double spending or cryptocurrency theft.

On the blockchain, a multitude of nodes, i.e. computers that keep a copy of the blockchain’s history, control transactions.

How do all these nodes validate a transaction in a decentralised way without conflicting, and maintaining the motivation to behave correctly?

In other words, how do they reach consensus in a secure way?

This is the heart of the Byzantine Generals Problem, a Game Theory case study.

It is a metaphor that allows us to better understand the challenge posed by consensus.

The problem is to allow four generals to make a decision and make their move in a coordinated way.

Here are the premises:

- Around a fortress there are 4 Byzantine generals (the nodes), each with their own army.

- They can decide either to attack (validate) or to retreat (refuse)

- Decision and action must be unanimous

- They cannot change their minds (immutability)

- They can send messages to each other to communicate the decision

The difficulty arises from the fact that messages can be lost, or one or more generals can betray others and send a message that puts others in danger.

In particular, a Byzantine Fault Tolerant system is characterised by a consensus mechanism that is not hindered if a network participant acts in a harmful way or does not participate.

This is crucial to make a blockchain scalable and efficient.

Proof-of-Work: longevity

Satoshi Nakamoto first solved the problem of Byzantine generals and distributed consensus by applying Proof-of-work to the Bitcoin blockchain. This same mechanism was then adopted by cryptocurrencies derived directly or indirectly from Bitcoin, such as Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Dogecoin and initially Ethereum.

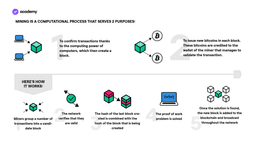

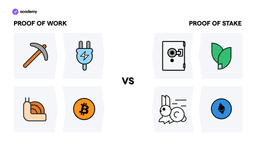

Proof-of-work is technically the proof of having spent more energy than anyone else decoding a cryptographic code generated by the protocol.

To achieve consensus through proof-of-work, nodes called miners compete to solve a cryptographic ‘puzzle‘. This is not a puzzle that requires any particular reasoning or logic, but to solve it a miner simply has to generate as many solutions as possible. The continuous generation of these solutions requires computational power (CPU) and thus energy.

The more computational power a miner employs, the more likely they are to solve the code, thus gaining the right to add the block to the Bitcoin blockchain and receive the transaction fees it contains, in addition to newly minted bitcoins.

This process carried out by miners is known as mining.

The reward that miners receive is the incentive to act in a fair manner throughout the network and not try to steal from other participants.

Even if a miner were to achieve enough computational power to take control of a sufficient part of the network (51%) to be able to influence its operation, they would have to choose between stealing other people’s bitcoins or validating a large number of transactions in order to get a high total reward.

In these cases, the protocol must guarantee that the lawful option is the most convenient.

Proof-of-Work Pros and Cons

- With Bitcoin, PoW has passed the test of time, keeping the network secure despite the latency (10 minutes to validate each block).

- In practice, the incentive invented by Satoshi has caused the emergence of Bitcoin mining pools that effectively control most of the network, thus making it less distributed.

- The high energy consumption, even with renewable sources, is a barrier to entry and a cost.

Proof-of-Stake: scalability and efficiency

It is not up to us to question whether Proof-of-Stake is more or less secure than PoW, but we do know that it is designed to be faster, more scalable and less energy-intensive. Polkadot and Cardano use PoS.

Instead of miners here we have validators, who prove their trustworthiness by putting at stake tokens in a locked wallet as a guarantee of their good behaviour.

By validating transactions and adding them to the blockchain, validators receive rewards. The way in which validators are selected is slightly different in each blockchain, but is usually fundamentally random. In some cases, the amount of tokens being staked also influences this.

Proof-of-Stake Pros and Cons

- One advantage is that to participate in such a blockchain, you only need an ordinary computer that simply has enough memory to store the blockchain history.

- The incentive to behave correctly is stronger because otherwise your stake is removed from the network through so-called ‘slashing’.

- The barrier to entry changes compared to Proof-of-Work because the purchase of very powerful hardware and high energy consumption is no longer required, but only having cryptocurrencies.

- This is why it is an often-criticised model: it’s not entirely inclusive. As mentioned above, each system requires a different trade-off.

On the other hand, the PoS incentive is perhaps cynical but effective: if I believe in a project enough to buy its cryptocurrency, it is not in my interest to harm its network. Conversely, if I don’t buy its cryptocurrency, I have nothing to lose from negative behaviour.

Ethereum: Proof-of-Stake vs Proof-of-Work

For all these reasons, Ethereum is gradually converting from the PoW mechanism to PoS by upgrading to version 2.0.

Faced with the choice of the ‘correct’ consensus mechanism, Vitalik Buterin reminds us that the spirit of the cypherpunks, i.e. the movement that led to the birth of Bitcoin, was idealistic, but also practical.

The cypherpunks were basically cryptographers and computer scientists who believed in decentralisation. Vitalik interprets the cypherpunk spirit, among other things, with the principle that it is better to create systems that are ‘easier to defend than to attack‘.

This is not only a question of philosophy, but also an efficient principle from an engineering point of view.

Proof-of-work does not respect this principle, as the cost of an attack is equivalent to the cost of defence: the loss is only in energy.

Proof-of-stake on the other hand increases the losses of those who go against the network: it punishes by slashing.

The other big advantage of PoS is speed. Vitalik Buterin himself, however, warns against focusing too much on speed, because given the blockchain trilemma, this will always mean sacrificing security and decentralisation.

Delegated Proof of Stake: inclusivity

Moving beyond the usual Bitcoin-Ethereum duo, let’s begin to think about the variety of possible consensus solutions.

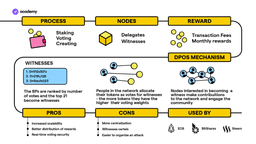

Let’s start with DPoS. This is the best-known variation of PoS, first iterated on by Dan Larimer, founder of Eos and Bitshares.

In this system, the entire network votes on who to delegate block validation to. Since validation is not an activity accessible to everyone, the possibility of delegation extends participation to more nodes.

Validators are called delegates, or witnesses, or block producers.

In order to vote, collateral must be staked, but this can be done through a staking pool on a service that is usually easy to use. Even small amounts can be deposited in staking pools.

When new transactions arrive, a limited number of delegates are randomly chosen to add the new block.

When a delegate validates a block they receive fees as a reward and give a percentage of it to those who elected them.

This consensus mechanism is adopted by Eos, and has similarities with the PoS of Tezos and Cardano, but there are differences.

Tezos also allows people to earn rewards by delegating their XTZs to a baker (validator), but the peculiarity is that these XTZs do not have to be blocked. They, therefore, remain liquid, which is why it is called Liquid Proof-of-stake.

Cardano, on the other hand, applies the concept of delegation only to staking pools. Delegation is not used to initially choose the validators, aka election, but only to delegate holders’ ADAs to staking pools. Any block producer in Cardano can end up validating a block, not a limited number elected at the beginning of the process.