What is Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS)?

June 7, 2022

8 min

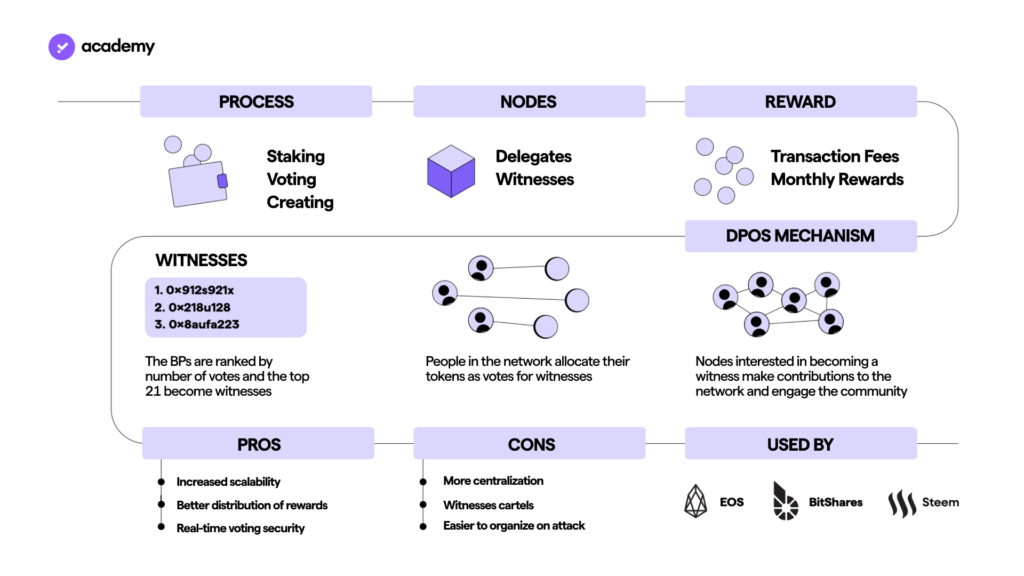

Decentralisation is fundamental in the cryptocurrency business model: distributing power on the blockchain among different nodes prevents censorship. In the absence of a central authority, however, it will need to be replaced by a shared agreement between peers. In a network, consensus mechanisms – protocols to determine the validity of transactions – are designed for this purpose: the most popular are Proof-of-Work (PoW) and Proof-of-Stake (PoS), but they too have limitations. Let us find out what they might be and how Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS) works: a third kind of consensus that could solve the problems of staking and mining.

From mining to staking

Movements of bitcoins will be entered immutably into its blockchain, but only after the network has reached an understanding on the legitimacy of the transactions. Their validation depends on the computational effort (Proof-of-Work) of the miners: high-performance hardware capable of sealing all information in packets, called blocks, with an alphanumeric tape called a hash, a gift from Satoshi Nakamoto.

The same happens in Ethereum, until the evolution into Ethereum 2.0 is completed. This version of ETH will in fact use the Proof-of-Stake mechanism to validate transactions. We have already talked about the changes introduced by PoS, but we could summarise them as a ‘green revolution’: consensus will no longer be based on an external resource, the energy consumption required for PoW, but on cryptocurrencies locked in staking.

Both protocols, beyond their differences, keep the blockchain secure by incentivising competition between nodes with rewards from block authentication. This, however, is not sufficient in itself to ensure either the efficiency of the system (speed and scalability) or its effective decentralisation.

The limits of PoW and PoS

Imagine agreeing among a multitude of peers on the truth or falsity of information, especially if it has economic value: the process will be as difficult as it is slow. This is particularly true in PoW, and it drastically reduces performance: Bitcoin cannot support more than 2-5 transactions per second (tps), Ethereum 12-25. However, BTC has historically been considered a store of value and can scale using Layer 2 solutions, while ETH gave birth to DeFi with its smart contracts.

Although some forms of Proof of Stake can bring the velocity to several thousand tps (see Avalanche and Solana), there is a second controversial aspect: decisions are often made by a select few, both in PoS and PoW, as well as in centralised finance. This goes against the very nature of cryptocurrencies.

PoW mining is, in fact, subject to the hegemony of an elite: the increase in the difficulty of the calculations results in small nodes giving up, unable to reach the output of more powerful hardware. Unable to compete alone, miners prefer to share resources and form ‘mining pools‘. Thus, in Bitcoin, historically the sum of the computing power of only 4 entities managed to reach 51% of the hash rate, while in Ethereum as many as 3 mining pools accounted for the majority of the computing power: the current forms of PoW create inequality.

The situation in Proof of Stake is similar: staking does not really justify prioritisation in validation, as it simply turns the cost of energy and hardware (PoW) into capital tied up. This consensus protocol, although often incorporating a random factor, confuses the virtue of nodes with their wealth.

Decentralisation of p2p models, however, is compatible with finance: Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS) is an attempt to return to that original goal of fully distributing systems, down to the root.

DPoS: power to the crypto people

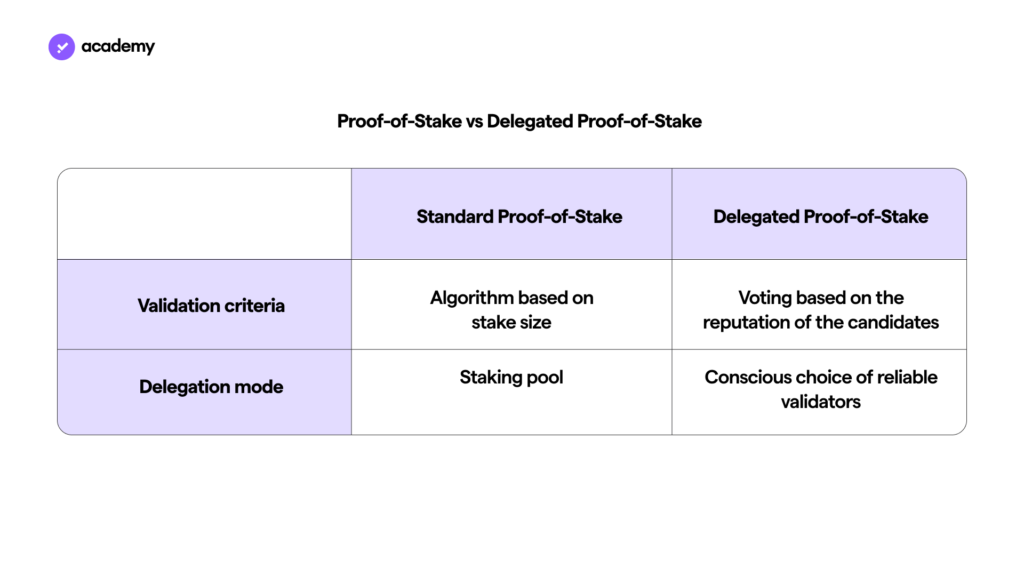

Prior to the introduction of the Delegated Proof of Stake consensus mechanism, the election of validators was never purely communal: the community, in some cases, may entrust the stake to certain entities or subjects, but this does not designate a vote, rather a collective participation in the certification of blocks. The PoS consensus algorithm, as mentioned, could then be integrated with a randomness factor, but this ‘mixed’ solution is different from the real DPoS.

DPoS has made it possible to actively vote for validators: the nodes with the best reputation will be in charge of preserving the integrity of the blockchain. The trustworthiness of a node is, according to some, a better indicator than the amount of wealth (PoS) or energy expenditure (PoW). In fact, the DPoS incentivises the good behaviour of block producers, as the community has the power to deprive them of administrative privileges.

How does Delegated Proof of Stake work? Anyone with a minimum amount of tokens can vote and contribute to the process of electing the delegates (or witnesses) who will handle the transactions. The delegates take turns in forging the blocks and distributing part of the rewards among the voters in proportion to their votes. The greater the stake, the greater the weight of the vote, but each coin should confer the right to speak, regardless of the amount: unlike Proof of Stake, this truly returns power to the network of individuals. The different forms of DPoS always have the staking of tokens as the basis of on-chain governance, but it is the conscious choice of the validators that restores subjectivity and democracy to the consensus protocol.

DPoS was conceived by Daniel Larimer in 2014: after talking to Sunny King, Delegated Proof of Stake was implemented in DEX Bitshares and in Steem, from which the social Steemit emerged. However, his most famous project is Eos.io, a blockchain for DApp development, based on the EOS cryptocurrency.

Cardano, Tezos: PoS with proxy

The new Proof of Stake protocols, as anticipated, have integrated the possibility to delegate tokens: small amounts can flow into larger stakes, so that validation rewards can be shared. The parallel with ‘mining pools’ is obvious: PoS network stakes would be equally centralised.

Indeed, without a minimum number of validators, as in DPoS, the risk is to hand over the blockchain domain to a micro-group of staking-pools. ‘Delegation’, in this case, does not solve the decentralisation problem, because it does not allow voting, but only participation in the monopoly. Having found out how Delegated Proof of Stake works, we now know that the 21, 101 or 301 delegates who take turns have equal minting rights, unlike in classic staking, where token entrustment is rather an option.

For example, Cardano‘s Ouroboros protocol allows the delegation of stakes, so that almost 3000 staking pools are formed, but a small subset of these control a total of 33% of the stake: an important number for the security of a PoS blockchain, called the Nakamoto Coefficient. Tezos‘ Liquid Proof-of-Stake, likewise, allows the delegation of tokens, which can be released at any time. There are more than 400 ‘bakers‘, but even here ⅓ of the holdings are held by just a few entities, 3 of which are centralised exchanges (Binance, Coinbase and Kraken).

DPoS is criticised for entrusting the security of the entire network to a small circle of representatives, but the Proof of Stake and Proof of Work protocols have made the ‘control room’ even more inaccessible. The number of validators in the DPoS is limited but trustworthy, making the networks faster and more secure.

Certainly, the risk of the formation of ‘cartels’ of delegates, acting for their own interests, is a reality, but less threatening than in PoW or classical PoS due to the minimum limit of validators. However, the apathy of stakeholders, who do not participate in the voting process, is an instance to be solved. This is why there is reward-sharing: in the ideal DPoS democracy, the candidate fulfils popular, constitutionally permissible demands and the voters enjoy the fulfilled promises.